Omar Sultan, former deputy minister of culture for Afghanistan, had a slogan when he was in office: “Taliban, you can break it. But as long as I live, I will rebuild it.”

Now, as part of that effort to rebuild his home country, he’s urging western leaders “not to take any quick decision to recognise the Taliban government”.

He said the international community should instead “put pressure on them for the education of girls”, so “women can work together next to the men”.

Sultan, who was speaking with archeologist Robert Parthesius of NYU Abu Dhabi during a recent public talk organised by the university, served in the government under former president Hamid Karzai from 2005 to 2011. He is credited with helping to reconstruct the cultural heritage sector in Afghanistan after the civil war and for taking crucial steps to staunch the looting of cultural heritage material at the time.

He was raised in Kabul in the 1960s and ’70s, and left to study archaeology in Greece, but was persuaded to return to Afghanistan in the 2000s, when he worked closely with the influential director of the National Museum of Afghanistan, Omara Khan Massoudi.

Sultan helped to secure funding from Unesco and the Greek government to rebuild the damaged museum and restore its collections, which had been reduced – owing to vandalisation, destruction or looting – by an extraordinary 70 per cent to 80 per cent.

Another focus of his was broadening the reach of the National Museum to reflect the rich spread of cultural heritage across the country. A network of 11 provincial museums was planned, with sites to be established in cities such as Mazar-i-Sharif, Kandahar, Jalalabad, Herat, Balkh and Bamiyan. Preparations for the project were continued until recently by the National Museum’s current director, Mohammad Fahim Rahimi.

“What I did in the last 20 years, it is like I’m in a dream,” said Sultan. “It’s like I am sleeping and seeing that we went back 20 years, and gave back Afghanistan to the Taliban.”

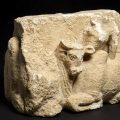

Sultan’s work in archaeology has underlined the uniqueness of the Afghan region. Because of its situation on trade routes and the number of empires it has belonged to, Afghan culture incorporates several forms and idioms. In one of Sultan’s excavations, for example, he identified a figure of Heracles standing behind one of a Buddha, in a striking meeting of Buddhist and Hellenistic traditions.

Faced with the potentially repeated situation of the Taliban’s suppression of culture, Sultan remains sceptical of the capacity of international agencies such as Unesco to protect the National Museum or other heritage sites on the ground. The possibility of widespread looting has returned because of a worsening economic situation and the lack of implementation of anti-looting laws. And although the National Museum has not suffered as before, international agencies are closely monitoring and publicising claims of further destruction throughout the country.

Cultural heritage is also threatened as an intangible asset – in the form of songs, knowledge and traditions – and Sultan emphasises that its strength is also intangible.

“When I was young, in Afghanistan, culture heritage united us,” he said. “The people in Afghanistan come from different tribes and different ethnicities, but when it came to culture, everybody was united. So that’s why I talk with all my friends and the Afghan and international people to do something about culture as world heritage.”

:quality(70)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/thenational/c451ae4e-15a2-4553-acaf-7a29665268c0.png)