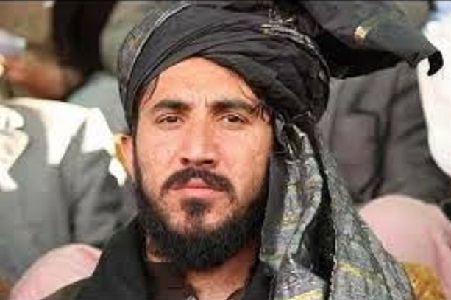

Pashteen

When he visits rural villages, fans shower him with rose petals. A YouTube user calls him a “rock star activist”. It’s an unlikely epithet for a 26-year-old from a remote, conservative Pakistani village who sometimes wears a traditional turban, reported NPR.

But in recent weeks, Manzoor Pashteen has risen to lead a fast-growing movement of thousands from Pakistan’s Pashtun minority, the country’s second-biggest ethnic group, who form roughly 15 per cent of the country’s 207 million people. Where few dare to criticise the army, Pashteen brazenly speaks.

“We have to identify the place that destroyed us,” Pashteen said at a recent rally. “It is GHQ!” he said, referring to military headquarters. The crowd cheered.

The destruction he refers to is the crushing of Pashtun homes during military operations and Pashtuns’ sense of humiliation at the hands of authorities. How Pakistan responds to Pashteen will have wide-ranging consequences. His heartland, a rugged territory known as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) near the border with Afghanistan, is one of the world’s most important geopolitical areas.

Now he is preparing for a large rally in the Pashtun-dominated city of Peshawar on Sunday. Activists hope a large turnout will show the military they cannot be suppressed.

If the Pakistani military tries to crush the movement surrounding Pashteen, it may complicate an already complex battle against militants in Pashtun areas, where the Pakistani Taliban are active and al Qaida once had its stronghold.

“It does have implications that go beyond one province in Pakistan, and go beyond Pakistan itself,” said Barnett Rubin, director of the Afghanistan Pakistan Regional Programme at New York University’s Centre on International Cooperation.

‘PEOPLE WHO SAY THOSE THINGS ARE KILLED’:

Pashteen is one of eight siblings from a family in South Waziristan, in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas. When he was a child, his family fled home four times as clashes erupted between the Pakistani military and insurgents.

His father, a schoolteacher, sent him to a military academy, far from where the army was fighting militants as part of the war on terrorism that began after September 11, 2001.

But during visits home, Pashteen said he became embittered. He alleges that thousands of Pashtuns were disappeared by the military and as many more were killed in bombings. He also alleges that soldiers deliberately killed innocents, including shepherds.

Like hundreds of thousands of other Pashtuns, his family was displaced for years during the worst episode of fighting between Taliban fighters and the military in his area in 2009. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reported that some 400,000 were forced to flee the Pashtun belt that year, but aid groups count millions displaced in years of fighting between 2004 and 2017.

When Pashteen’s family finally returned in 2016, they found their home ruined, their books looted, and their lands studded with landmines. And, he said, they endured humiliation at army checkpoints.

Finally, he decided to speak out. “What would the next generation think if we faced brutality and oppression – but we didn’t even raise our voice? What message are we giving? They would think we are people without honour,” he recalled telling his father. “My father would agree, but he would say: ‘People who say those things are killed.’”

‘FROM 22, WE BECAME 22,000’:

Pashteen emerged as an activist for his tribe, the Mahsuds, in 2014. It took another four years for him to come to prominence, in January, after the death of Naqeebullah Mehsud, an aspiring model from his tribe. Mehsud was shot dead in Karachi, and a senior police officer stands accused in his death. Pashteen led demonstrations in Islamabad to protest Mehsud’s killing.

The police hinted Mehsud was a militant, something his family and friends deny.

The “atmosphere around Pashtuns has become toxic” in Pakistan, said Ammar Ali Jan, an assistant professor at Punjab University in Lahore. “They have been [the] centre of the war on terror,” he said. And now, “it’s almost projected as a Pashtun problem: violence, terrorism, religious extremism.”

During the sit-in he led in Islamabad, Pashteen said he realized something bigger than a single protest was happening. Pashtuns from different tribes began joining in. Demonstrations erupted in other Pashtun areas. His own experiences, he realized, were echoed across Pakistan.

“From 22, we became 22,000,” he said.

Since then, activists have coalesced around Pashteen, forming the Pashtun Tahafuz [Protection] Movement. Its base is students and professionals, including doctors and lawyers. They run a Facebook group called “Justice for Pashtuns”. Pashtun singers croon about the movement. Even Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai tweeted her support.

‘THERE IS NO WAR ON TERROR. THERE IS ONLY TERROR’:

In Pashteen’s whistle-stop rallies, lectures and meetings, he has emboldened others to articulate their grievances against the military, Pakistan’s most powerful institution, and its widely feared Inter-Services Intelligence agency. They do even though they say they are vulnerable to harassment, abuse, disappearance and even death.

“People started saying: this is also what we held in our hearts,” said Izhar Yousefzai, 22, a Pashtun student. Yousefzai said he once dared not speak. “When Manzoor Pashteen raised his voice, I found a companion. I joined him.”

Most explosively, Pashteen and his movement accuse the army of sheltering some militants — specifically, the Haqqani Network, which is affiliated with the Afghan Taliban — in Pashtun areas.

“They are feeding the Taliban, and they let them reside in military areas,” Pashteen said. Meanwhile, “they are raising slogans about the war on terror.”

Pashteen and his followers say they have paid the price of that policy, enduring drone strikes, clashes, acts of terrorism by insurgents and displacement.

“There is no war on terror. There is only terror,” Pashteen said last month in Peshawar, near the border with Afghanistan. He was with other activists, discussing how to arrange a rally in April. “We are standing eyeball to eyeball,” said Pashteen of the army and his movement.

‘A MASSIVE MOVEMENT OF PASHTUNS’:

Rubin of New York University said the Pashtun movement is articulating views that were once whispered.

“It’s quite new that they would do that so openly,” Rubin said. “It turns out there’s a massive movement of Pashtuns in Pakistan who are saying what I have heard in private for many years.”

The US has also accused Pakistan of harbouring militants. President Trump accused Pakistan of offering “safe haven to agents of chaos, violence and terror” in August. The US has since pressured Pakistan by cutting off most military aid and punishing the country financially.

Pashteen wants to pressure Pakistan internally, said Mohsin Dawar, a columnist and activist with the movement. It would have a different resonance from pressure exerted by the US and the West, he said.

“If there is a local resistance, or a local, strong, confrontation, [the military] won’t be able to pursue whatever they have been doing the last 15 years,” Dawar said.

Pakistan denies it harbours militants. Retired air marshal Shahid Latif said Pashteen’s claims were “an overstatement”, but said he was sympathetic.

There have been years of “leniency” by the Pakistani military toward the Haqqani Network, he said, because its members fought as anti-Soviet mujahedin during the Soviet war in Afghanistan of the 1980s.

“They are the people who were in league with the security forces, back when we were fighting our jihad in Afghanistan,” he explained. “So actually you can trace all the troubles starting from that time, and since they were fighting alongside our security forces and they were doing something that was kind of arranged by the state. So they expect some kind of a lenient treatment — even today.”

Army commanders initially negotiated truces with some Haqqani militants instead of fighting them, he acknowledged. But, he said, things have changed: “Security forces are now not in any mood to grant them this leniency.” Going after the Haqqani group has been a key demand of US administrations.

‘A TREMENDOUS OPPORTUNITY’:

Pashteen’s Islamabad demonstration disbanded after authorities vowed to meet some of the protesters’ demands, including speeding up de-mining efforts and removing some army checkpoints in Pashtun areas.

The government responded in other ways, too: Rao Anwar, the police superintendent suspected of killing the aspiring Pashtun model in Karachi, appeared in court on March 21, after weeks in hiding. He is being investigated for involvement in the killing, and Pakistan’s army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa assured Mehsud’s father that the army supported the family in its pursuit of justice.

Rubin said Pakistan should view the Pashtun movement’s demands for better treatment as an opportunity.

“It means that they have a tremendous opportunity to unite their country’s various ethnic groups through the means of democracy and federalism,” he said.

But there are darker signs. Police registered a criminal case against Pashteen for criticising the government and security agencies, Pakistani media reported. Dawar, the political activist, said he was removed from his position as head of the youth wing of a secular Pashtun political party, which he claimed in a WhatsApp message was “under an immense pressure from the military”. And activists claimed a prominent member of Pashteen’s movement, Sadiq Achakzai, was seized by security agencies in Quetta.

“The government needs to end its longstanding discriminatory laws and practices against Pashtuns and act to end hostile attitudes toward them,” Human Rights Watch said March 13. “This process could start by dropping the criminal cases against Manzoor Pashteen and other protest leaders wrongfully charged, fully investigating and fairly prosecuting those responsible for Naqeebullah Mehsud’s death, and letting Pashtun voices be heard.”

Pashteen told NPR regardless of how he was treated, he would remain non-violent. But if security forces crack down, “I can’t control how other Pashtuns will act,” he said. No longer, he insisted, would Pashtuns be like tissues “that the Pakistani state uses – and then throws away”.