Courtesy: DW

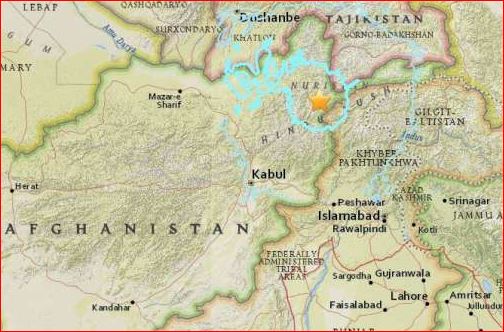

Most Afghan and Pakistani Pashtuns have cultural ties that date back centuries. The Durand Line border has failed to separate them and restrict their mobility. Can Pakistan’s new border control measures be successful?

Every day, thousands of Afghans and Pakistanis cross the Durand Line – the 2,430-kilometer (1,510 miles) long boundary established by the British during their colonial rule.

The Afghan government does not recognize the Durand Line as the official border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, nor do ethnic Pashtuns who live on both sides of the border and share historical, cultural and family ties.

The Pashtuns can easily travel back and forth across the border, but the deteriorating political ties between the two countries are now causing them problems.

Ties too deep to sever

For Afghan citizen Haider Khan, the rift between the two nations and the tightening of border controls are affecting his mobility.

“I travel to Pakistan every week. I leave Kabul every Thursday and come back on Saturday,” Khan told DW. Khan believes it wouldn’t be that easy in the future.

Khan works as a cook in a restaurant in Kabul. The 35-year old belongs to the Pashtun Shinwari clan based in the Khyber valleys and the Spingar (White Mountain) on both sides of the Durand Line. Like most people who cross the border frequently, Khan has no travel documents. He relies on his tribal connections and cultural bonds to ensure an unhindered journey.

But why does Haider Khan travel to Pakistan so often?

“Afghanistan is going through a rough time, and Pakistan is relatively safer. I prefer to keep my family in Pakistan but I cannot completely cut off ties with my fellow tribesmen in Afghanistan,” Khan explained.

New measures

There are thousands of people like Khan who work in Kabul and have their families in Pakistan’s northwestern areas. And there are those who have families in Afghanistan but they work or study in Pakistan.

These people find themselves in a deeper trouble following the stern border control measures imposed by Pakistan on June 1, 2016. As per new regulations, people without a valid visa would not be allowed to enter Pakistan. The new measures affect thousands of tribesmen, many of whom do not even possess a passport.

The introduction of new border measures is part of the Pakistani army’s National Action Plan (NAP) against terrorism. Islamabad believes the Taliban and other Islamic militants use the porous Afghan-Pakistani border to launch attacks in both countries. There is international pressure on Islamabad to act against the insurgents.

Now even the Afghan refugees, who have been living in Pakistan for decades and have a Proof of Registration (PoR) from the Pakistani government, would not be allowed to return to Pakistan after paying a visit to Afghanistan.

But experts say the ties between the Afghan and Pakistani Pashtuns are so deep that any border control mechanism has a very limited chance of success. Also, thousands of people across the border are tied up with transportation, hotel business, logistics and different services that thrive on the cross-border movement.

“I don’t know what to do now. I possessed Pakistan’s identification card but the authorities have refused to renew them. Technically, I am a stateless person now,” said Khaista Gul of the Momand tribe, who lives between Afghanistan and Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). Gul runs a family business in the Pakistani city of Peshawar.

But the Afghan and Pakistani Pashtuns know the border restrictions are temporary and that they will find a way to deal with them.

Terrorism and trade

Apart from the border control measures, cross-border shelling by Pakistani security forces has also restricted the tribesmen movement across the Durand line.

Juma Khan, a resident of Afghanistan’s eastern Kunar province along the border, says the constant bombing by Pakistan’s border forces must stop. “Things were different in the past; we could freely move from one side of the border to other. Now we have to be careful,” Khan told DW.

The movement across the Afghan-Pakistani border also generates revenue for both Afghanistan and Pakistan. The two countries exchange goods and services worth some 2.7 billion euros ($3 billion) annually across the Durand Line. Despite the illegal trade and smuggling, the two countries benefit a great deal from the cross-border movement.

Suleman Layeq, a renowned Pashto poet, says that even if the aim of the border restrictions is to curb the movement of terrorists, they would only create problems for the ordinary tribesmen while the terrorists would move freely.

The 85-year-old poet believes that no border can divide Afghan and Pakistani Pashtuns as the Durand Line can’t be compared to other international borders.

“It is not up to the governments to decide whether the Pashtuns follow the rules or not. Only the people living in the area have the right to decide,” Layeq told DW.